Rashomon Effect

Different people have different interpretations of the same event.

By Hamzah Javaid

November 11, 2022

Different people have different interpretations of the same event.

Rashomon Effect

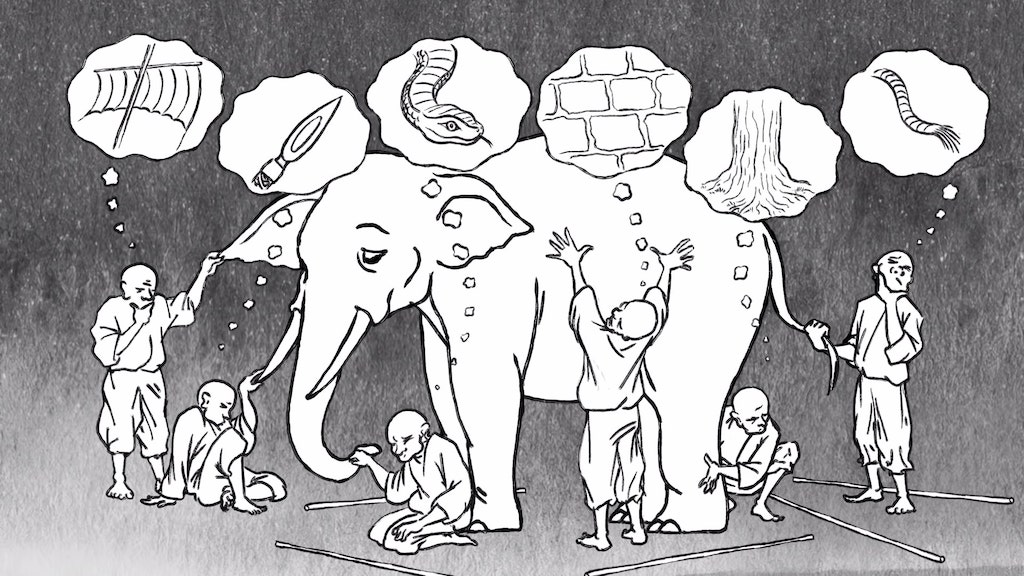

The Rashomon effect, a term derived from Akira Kurosawa’s classic film Rashomon, refers to the phenomenon where different people have different interpretations of the same event. In the movie, four different witnesses recount the same murder from their own perspective, each one presenting a completely different version of what happened. This effect is not just limited to movies; it can be observed in real-life situations where people’s subjective experiences influence their interpretation of events.

- Anne Duke in her book Thinking in Bets writes:

“We’ve all experienced situations where we get two accounts of the same event, but the versions are dramatically different because they’re informed by different facts and perspectives. This is known as Rashomon Effect, named for the 1950 cinematic classic Rashomon, directed by Akira Kurosawa. The central element of the otherwise simple plot was how incompleteness is a tool for bias. In the film, four people give separate, drastically different accounts of a scene they all observed, the seduction (or rape) of a woman by a bandit, the bandit’s duel with her husband (if there was a duel), and the husband’s death (from losing the duel, murder, or suicide).”

The Rashomon effect is a critical mental model that can help us understand how our perceptions and biases shape our understanding of reality.

“The Rashomon effect reminds us that our minds filter the information we receive, shaping our perceptions and influencing our decisions.”

One of the most significant implications of the Rashomon effect is that it highlights the subjectivity of truth. As the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche once said, “There are no facts, only interpretations.” This statement is particularly relevant when it comes to the Rashomon effect because it shows that our understanding of reality is not absolute but rather influenced by our personal experiences, cultural background, and beliefs.

- Morgan Housel, in his essay The Psychology of Money, writes :

“Your personal experiences make up maybe 0.00000001% of what’s happened in the world but maybe 80% of how you think the world works. If you were born in 1970 the stock market went up 10-fold adjusted for inflation in your teens and 20s – your young impressionable years when you were learning baseline knowledge about how investing and the economy work. If you were born in 1950, the same market went exactly nowhere in your teens and 20s.When everyone has experienced a fraction of what’s out there but uses those experiences to explain everything they expect to happen, a lot of people eventually become disappointed, confused, or dumbfounded at others’ decisions. Keep that quote in mind when debating people’s investing views. Or when you’re confused about their desire to hoard or blow money, their fear or greed in certain situations, or whenever else you can’t understand why people do what they do with money. Things will make more sense.”

The Rashomon effect also has practical applications in fields such as law and journalism. In courtrooms, for example, witnesses are often called upon to provide their version of events, but the Rashomon effect suggests that their testimony may not always be reliable. Journalists, too, must be aware of the Rashomon effect when reporting on events as their own biases can influence their interpretation of the facts.

However, the Rashomon effect can also be a valuable tool for self-reflection. By recognizing our own biases and the subjectivity of our understanding of reality, we can become more open-minded and better able to appreciate the perspectives of others. As Safal Niveshak writes, “If we can view the world through the eyes of others, we can gain new insights and see things from a different perspective.”

Fooling ourselves

Fooling ourselves is the easiest thing to do.

Commenting on scientific truth-seeking, Richard Feynman says —

A kind of utter honesty — a kind of leaning over backwards. For example, if you’re doing an experiment, you should report everything that you think might make it invalid — not only what you think is right about it: other causes that could possibly explain your results…

Are we fooling ourselves looking into the mirror.

Concluding remarks

- Duke writes:

“Even without conflicting versions, the Rashomon Effect reminds us that we can’t assume one version of a story is accurate or complete. We can’t count on someone else to provide the other side of the story, or any individual’s version to provide a full and objective accounting of all the relevant information. When presenting a decision for discussion, we should be mindful of details we might be omitting and be extra-safe by adding anything that could possibly be relevant. On the evaluation side, we must query each other to extract those details when necessary.”

In conclusion, the Rashomon effect is a crucial mental model that reminds us of the subjectivity of truth and the impact of our biases on our understanding of reality. It highlights the importance of being open-minded, self-reflective, and willing to consider different perspectives. By doing so, we can become better decision-makers and more empathetic human beings. As Kurosawa himself said, “Human beings are unable to be honest with themselves about themselves. They cannot talk about themselves without embellishing.” It is only by recognizing and confronting this tendency that we can hope to gain a clearer understanding of ourselves and the world around us.